The Haldiram saga started when the family patriarch Haldiram started selling bhujia, a popular crispy snack, to the locals of Bikaner (Rajasthan) in 1918. Over nearly a century, the popular branded packaged foods company has expanded steadily both in India and overseas, in the process surviving family factionalism, changing consumer tastes, increased competition and US regulatory heat. Bhujia Barons is both a story of family intrigue including a murder plot, and the growth of Haldiram’s into a 5,000 crore business empire. The following is an edited extract from the book authored by Pavitra Kumar.

Notorious stories of bribes, blackmail and bullying abound in Hindi films and are often heard of in the form of gossip in business circles that most ordinary people are not privy to. One is always curious to read about businessmen, and the lengths they are willing to go to expand their empires. These leave us with a sense of amazement that they pulled it off, indignation that they managed to get away with it, and a mixture of disgust and admiration that they had the mettle to actually think of such deeds and carry them out. Prabhu Shankar Agarwal was one such businessman. Over the years Prabhu had received a lot of bad press for myriad reasons. Where the press was concerned, he had more than earned his disrepute.

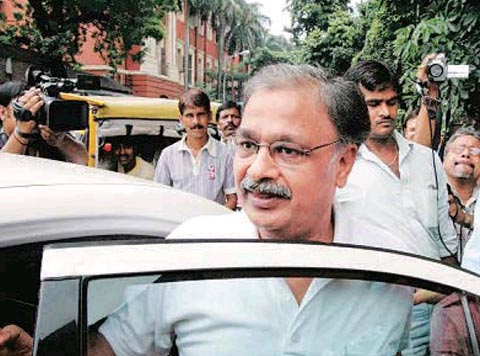

The journey to Kolkata to meet Prabhu, Rameshwarlal’s eldest son, was fraught with nerves and trepidation. In Kolkata, he was notorious for his boisterous ways and for allegedly being unafraid of bending the law to achieve his goals. The man seemed to have a lot of clout in the state and the thought of meeting him face-toface and asking him difficult questions about his life and business, was daunting.

Prabhu, the 56-year-old owner of the famous Haldiram Bhujiawala business in Kolkata, has gained quite a reputation in business circles in Kolkata and nationally. On 5 June 2005 Prabhu was arrested for allegedly attempting to murder a teashop owner in order to gain access to his land, which was directly in front of a food mart that he was building. The charge sheet was filed a year later. Prabhu was tried in a fast-track court, declared guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment by judge Tapan Sen on 29 January 2010. Spending several months in jail, however, did little to affect his business. Haldiram Bhujiawala, under the guidance of this dynamic leader, has continued to prosper. Prabhu was the proverbial elephant in the room during every conversation with the Haldiram family. In spite of being far from Bikaner and Delhi, he seemed to be present in spirit among them through words both spoken and unspoken. While newspaper articles had portrayed this businessman as a murderous convict lacking scruples, one naturally expected family members to defend and justify his actions. But it was not so. In fact, the members of the family in Delhi and Bikaner were distinctly uncomfortable about questions on Prabhu and made no move to defend him. With rumours abounding, and having heard multiple stories about him, it would have been really easy to form preconceived opinions about the man. However, landing in Kolkata forced me to realize that up to that point, the man had been an enigma—a great businessman, shrewd and tough, capable of going to great lengths to grow his business, maybe even murder!

Prabhu inspired discomfort, fear and distaste among his family members, yet there was also an underlying awe for his persona and bold actions. While largely diplomatic, family members almost couldn’t help themselves as they divulged their feelings about the owner of the Kolkata Haldiram Bhujiawala. Words such as ‘greed’, ‘selfishness’, ‘unpredictable’, ‘temper’, ‘ambitious’ and ‘secretive’ found their way into the descriptions. But as the conversations deepened and family members felt more and more comfortable, reluctant praises such as ‘dynamic’, ‘keen business acumen’, ‘strong’ and ‘visionary’ tumbled in. The man was a paradox, both notorious and private, all at once. It is said that nobody knows which version of him they would meet on any given day.

At 11 a.m. sharp, on the designated day, checking in with the receptionist on the second floor at the Kazi Nazrul Islam Avenue showroom, it was impossible not to feel nervous about meeting Prabhu. This was Haldiram Bhujiawala’s largest showroom in the city and also the headquarters of the company. Waiting in the reception area as the malik, or owner, finished his rounds of the ornate showroom floor below, one couldn’t help but admire the beautiful painting covering the wall behind the receptionist’s desk, depicting the opulent showroom building, glorious in the pink rays of the dawn, decorated by a single ornament, the ‘Haldiram Bhujiawala’ signboard. The outlet was definitely lavish compared to showrooms in any other city, including Delhi. There seemed to be something slightly classy about it, which was reflected in the painstaking way in which trays of sweets and snacks had been arranged in alcoves and on stations, brightened by flattering yellow lighting in the right places. The showroom was large with a huge room on the side, serving as the restaurant. Unlike the other Haldiram brand showrooms in Nagpur and Delhi, this one seemed to be catering to a more high-end crowd, with sophisticated tastes. However, Prabhu would vehemently disagree. “Look at our reasonable prices,” he said in justification, claiming that the middle-class Indian was their primary target customer group. He strongly believed his target customers had sophisticated tastes.

While store design and in-store branding had hardly ever been an overarching strategy, nonetheless, they reflected Prabhu’s innate understanding of aesthetics and desire for great presentation. An entourage of men barged into the reception area. The short, portly man in the front of the group exuded a bustling energy that swept up everyone in its path. Prabhu had a very cheerful air about him, with sparkling bright eyes and a keen friendly manner. Having shaken my hand and introduced himself with a beaming smile on his face, he apologized for making me wait and asked me to follow him into his office. He seemed involved in all the intricate details of his business, discussing the design of a new workshop floor, arguing with an engineer about the dimensions of a required machine and working with his secretary to clear his schedule for the next few hours. Finally, he offered me his undivided attention.

Prabhu came across as an impatient perfectionist with both vitality and grace. He was a man of action and seemed to be able to multi-task even while answering questions. Unlike his Delhi and Nagpur cousins, he seemed to also have a sharpened media awareness, compelling him to put his best foot forward in front of outsiders. What piqued my curiosity was that in spite of his friendliness, he also seemed to exhibit a wariness of unknown entities. Sometime during our conversations, he confessed that he had been watching me silently on the showroom floor before I made my way to the reception area. He had watched me admire the stands, talk to his employees and formed certain opinions about me, before he came to greet me with great aplomb. It subtly gave away the man’s lack of trust in most people. However, it also indicated that Prabhu was always primed for battle and never as unassuming as he made himself out to be.

Slightly wary, he answered almost ever y question posed to him with a coun te r-qu estion. It seemed he had come prepared not to say anything politically incorrect. While most of the other Haldiram progenies had started conversations with a slightly humble, diplomatic opening such as, “What can I tell you that others haven’t already?” Prabhu constantly asked, “What did they tell you in Nagpur and Bikaner? I will be more comfortable to talk to you once I know what they said.”

Born in 1959 in Kolkata, Prabhu had lived his whole life in the bustling post-colonial city. A few years younger than even his cousin Manoharlal, Prabhu had missed most of the early action in Kolkata. By the early 1970s, when Prabhu began helping around in the shop and learning about the business, he was already heir to the largest outfit of the Haldiram businesses since at that time the Kolkata branch made the highest margins and the most sales compared to Bikaner and Nagpur.

Everything he had learnt about entrepreneurship and making bhujia, he had learnt from his father, Rameshwarlal. In spite of never having lived in Bikaner, unlike every other Agarwal man from his generation or previous ones, Prabhu had imbibed the same ingenious skill of identifying spices and mixing fabulous snacks from scratch.

In fact, when young, his love for the family business constantly stole him away from regular studies. He studied up to the higher secondary level at Shri Didu Maheshwari Panchayat Vidhyalaya in Bada Bazaar. While he found every excuse to skip classes and help out in the shop’s kitchen, his father rarely rewarded him for his enthusiasm. “I was given a lot of tough love for trying to join work that early. My father was not happy because unlike him, he wanted me to study further and gain a proper education.”

“However, I was always the student who was first from the bottom,” said Prabhu with a guffaw. While largely uninterested in studies, Prabhu was deeply affected by the words of one Hindi professor whom the children called RD out of affection.

“RD always said, ‘The man who works never loses. The reward will find you some day, somehow.’ These words left a lasting impression on me and have ever since always proved true, at least in my life,” he said.

He began by working at the cash counters, helping with billing and accounting. His knack for numbers and understanding of the use of promotions such as discounts to make a profit quickly shone through. In fact, even today, he readily admits that practical education behind a cash counter takes someone way farther than any structured educational programme can.

When asked how long his training lasted, he said with a smile, “It’s going on even today.” More seriously, he confessed that while he had learnt the ability to taste for ingredients, manage the business and remain strong in the face of major challenges from his father, Rameshwarlal, he had not acquired his acute desire for success from him. Rather, he believed that he had greater ambition than most men in his family and that men from his father’ s generation had not been truly forward looking. However, he couldn’t help but be proud of his father’s skill at namkeen- making.

It is claimed that Rameshwarlal was the best taster in his family, for his time. He could tell you what type of oil had been used in a dish including insane amounts of detail around those ingredients. For instance, if he had identified that peanut oil had been used, he could almost accurately guess what percentage of moisture the original peanuts had contained. “They used to call him Laboratory,” said Mahesh, Prabhu’s younger brother and owner of Pratik Foods Ltd, with pride. Rameshwarlal had also learnt a great deal about the Bengali market and the tastes of the customers during his years in Kolkata. He was known for his calm, collected temperament, and both sons admit that they had never seen their father exhibit any signs of stress in spite of demanding conditions at work.

Unlike his brother Moolchand, Rameshwarlal was industrious and ambitious at least to the extent of wanting to run a profitable and growing enterprise. He, however, according to his sons, lacked strategic foresight or ambition.

“Men of those times, they did not have dreams. They were so busy keeping their head above the water and tending to their daily responsibilities that they could never plan for the future. For my father, growth happened through a one-plus-one-plusone organic forward movement or rather through serendipitous moves,” said Prabhu. Mahesh seemed to have a differing viewpoint from his brother. “Father wanted to grow the business but not so much that it would become an uncontrollable obsession. He always advised us to work as much as required to have a happy, comfortable life,” he said. As kids, Prabhu and Mahesh would go to the showroom every day unless they were faced with highly extenuating circumstances. They were incentivized by money, of course!

Rameshwarlal said that if they went to the shop and spent even half an hour there, they would earn 50 paise to a rupee. In this way, the boys earned their pocket money but also subconsciously began to understand the mechanisms of running a shop and the needs of the customers. “We used to call it galle ka paisa since it came from the petty cash drawer. If we didn’t go to the shop, we wouldn’t receive the money. At that age, it was a very tempting proposition. Whether we helped out at the shop for five minutes or a whole hour, we always received the same amount. It was a very clever ploy.

“I suppose father hoped that our natural curiosity would be piqued with time, and boy was he lucky that it did,” said Mahesh. While Mahesh spoke about the pocket money, Prabhu’s recollections give an insight into what makes him tick as a person. “It was also a great thrill when the staff called us ‘malik’ at that young age and treated us with immense respect, the same that was given to the big boss! It made us feel important. I think the whole experience also taught us the value of money—that it was in reality always tied to something,” he said. Perhaps it was then that he also realized a mesmerizing truth, that money was also directly linked to power. However, while he was alive, Rameshwarlal never allowed his sons to abuse the power of their growing inheritance. Like his father and brothers before him, he had also imbibed the inherent sense of investing profits back into the business.

Money earned from the business was not meant to be squandered away on luxuries, but instead ploughed back to further nourish the business. All the Haldiram progeny seemed to be very proud of this trait, believing that it differentiated them from several other business families that never made it. A shared principle was that man should have control over money, not the other way around.

“I remember when I was really young, my father and I were walking down the street and I came across some raffle tickets where you could win something if you got the lucky number,” recalled Mahesh. “I was very excited and unabashedly begged him to buy me one.”

“But he said, ‘You’ll pull the ticket but you don’t know what you’ll receive. Instead, why don’t you tell me exactly which toy you want from the lottery items box and I will buy it for you? That is a guarantee for getting what you want. Why gamble when you can be sure?’ This stayed with me for a long time. Destiny is of our making and luck has nothing to do with it.”