There's a direct link between GDP growth and energy consumption. That means demand for oil and gas grows whenever GDP growth accelerates. India's long-term demand for these two fuels will rise steadily. Dealing with that demand implies sensible policy making and it will also lead to long-term trends that affect multiple sectors, from energy to transport and fertilisers.

India is the third-largest oil importer in the world and it is slated to become the second-largest or largest importer over the next decade to 20 years. This is mainly because India has high GDP growth rates and low per-capita energy consumption.

But domestic production of oil and gas has stagnated. In fact, it's possibly falling. In 2016-17, India produced 36 million tonnes of crude, a decline compared to the 37 MT in 2015-16. Production was around 36.8 MT in 2012-13, so there's been stagnation. Similarly, India produced a gross 31,897 million metric standard cubic metres (mmscm) of domestic gas in 2016-17, which was less than the 32,3250 mmscm in 2015-16. Net gas production was 30,850 mmscm, which was also a little less than that in the previous year.

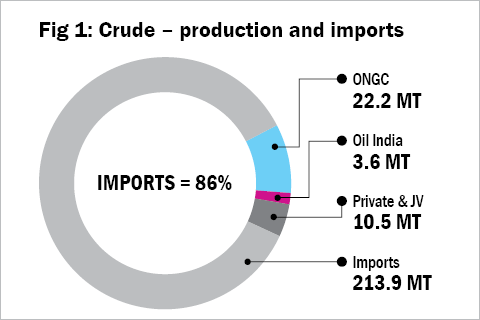

India imports 80 per cent of its oil (see Figure 1) and about 40 per cent of its gas. The import dependency will grow. In 2016-17, imports were about 5.5 per cent higher than those in 2015-16. However, India refined 242.7 MT of petro products in 2016-17 and that's 5 per cent higher than the 232 MT of products in 2015-16. India is a major exporter of petro products. In 2016-17, it exported 65.5 MT of products, higher than the 60 MT exported in the prior fiscal. This is very useful since these exports earn forex and help to balance energy imports to some extent. India's product imports largely consist of LPG; gas imports amounted to over 12 MT of oil equivalent in 2016-17.

Domestic demand (as opposed to imports for refined re-exports) was around 194 MT in 2016-17, up from 185 MT in 2015-16. Crude imports have grown at around 3-5 per cent annually over the past five years (there are large variations, with a maximum rise of 11 per cent in 2015-16). It's reasonable to expect demand growth to continue growing at 3-5 per cent if GDP grows at 7 per cent plus.

Gas demand is harder to judge, though it's grown consistently. There is almost certainly suppressed demand, and the mix also varies due to pricing and availability. There's a formula for pricing domestic gas but imported LPG is cheaper. If gas (LPG or LNG) were more easily available, it would be used more for cooking and transport, as well as power generation. It's likely that gas demand will spike sharply if the logistics of gas transport (pipelines and gas-distribution agencies) improves.

So here are the trends and the likely policy stances.

1. Import dependency will rise through the foreseeable future. This will affect India's diplomatic stance and leave the nation exposed to geopolitical upheavals.

2. Domestic production will be encouraged, along with better infrastructure such as LNG terminals, pipelines, pumps, etc. Smart policy-making is required to ensure efficient distribution channels.

3. India is building a strategic oil reserve to store crude and smoothen out volatility in prices. In the event of supply disruptions, that reserve will be vital.

4. Refining capacity will grow and surplus will remain. Indian refiners, especially the private-sector ones, have decent refining margins and are big exporters. Higher exports of products will help to balance imports.

5. Domestic prices will remain dependent on global trends and will also be influenced by socio-political considerations. Apart from the direct impact of fuel prices, fertiliser subsidy is a sensitive issue and fertiliser costs vary with gas prices since that's the raw material.

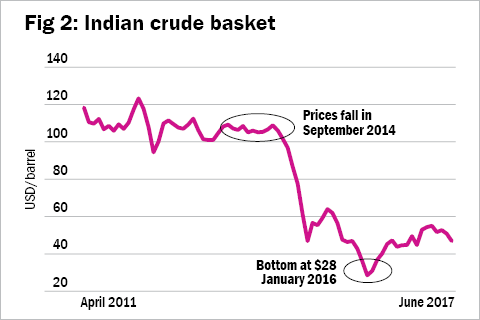

India has been very lucky since late 2014. The Indian crude basket is a mix of Oman and Dubai sour (high sulphur) grades and Brent (low sulphur) crude. Prices were above $100/barrel for several years. The price started dropping in September 2014 and hit a low of $28/barrel in January 2016 (see Figure 2). The price has stayed relatively low since then. The annual average cost is revealing.

This has yielded many benefits. At the macro level, it means a lower trade deficit. The government also has the leeway to decontrol retail prices to a large extent and to allow PSUs to charge profitable retail prices. Low prices have also allowed governments (Centre and states) to impose taxes to raise revenues. Low prices have also emboldened the private sector to consider retail; earlier attempts to set up petrol pumps were aborted due to high prices.

If prices climb above a certain threshold, the government may impose price controls again. It would also have to cut taxes and perhaps revert to the earlier system of forcing PSU retailers to sell at a loss and doling out subsidies.

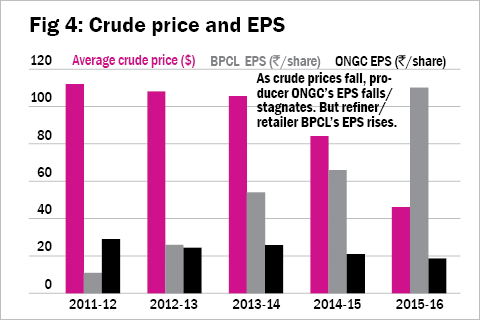

Refiners and marketers always gain when prices are low and India will remain largely a refining centre. Conversely, producers lose out when crude and gas prices fall.

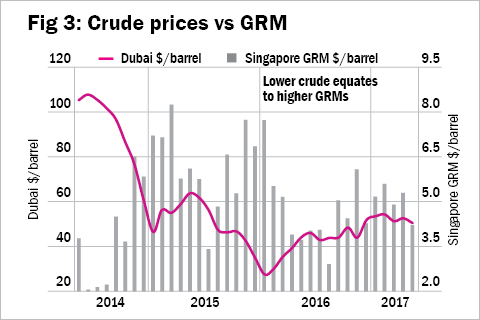

An indicative chart of Singapore gross refining margins for Dubai crude (the Singapore GRM is a benchmark that averages GRM for multiple Asian refiners) versus Dubai crude prices indicates how GRMs fluctuate inversely with price changes (see Figure 3).

As crude prices drop, GRM rises. This makes intuitive sense as well since refiners cannot always pass on higher crude prices. Incidentally, RIL consistently has much higher GRMs than Singapore. But most Asian GRMs travel in the same direction.

Oil majors attempt to integrate end to end, from exploration and production to retailing at petrol pumps, to remain profitable whatever the crude price. But Indian firms have not yet managed this, although most companies have stated such ambitions.

Reliance Industries has presence in exploration and production (E&P) and refining but it doesn't have retail outlets (that's on the agenda). ONGC has E&P and refining but not much retail/marketing. Oil India is basically E&P. BPCL, HPCL, Indian Oil are all refiner-marketers with retail outlets but no E&P. GAIL is almost purely gas transport and marketing. Petronet LNG is a transporter/marketer as well. Cairn is in E&P.

The profitability of refiner/marketers obviously rises when crude prices are down. Vice-versa, profitability of E&P players falls. Take a look at the earnings trends in ONGC versus EPS in BPCL, compared to crude prices (see Figure 4).

So long as oil prices remain reasonably low, India will be in good shape. Gas prices are negotiated but again tied to oil prices in some respect. Costs also vary largely in terms of transportation distances.

Massive investment opportunities may exist across the whole value chain. There will be some thrust into E&P, though this is a gamble. Government policy envisages changes to make the HELP (Hydrocarbon Exploration & Licensing Policy) a revenue-sharing regime with tax breaks and easier access to geological data. Producers of gas from difficult places (deepwater, ultra deepwater, etc.) will also get pricing freedom. Shale and coal-bed methane are two sectors which have barely started functioning. E&P equipment companies (rigs) and logistics providers (transport, etc.) and civil/construction firms working in this space would be worth looking at.

Refiners, as mentioned above, will expand. So will retail networks if prices remain decontrolled. Companies will try to integrate across value chains. There's play in pipelines and city gas distribution. Again, policy changes are happening there. If gas becomes more freely available at reasonable prices, more automobiles and trucks will switch to gas.

The fertiliser sector may also see changes. Fertilisers have complex subsidy schemes. Subsidies can be rationalised if gas prices are stable and predictable. Ideally, subsidies should be removed but that won't happen because farmers are an important political constituency. Gas and naptha power plants could also make a comeback.

So it's a rosy scenario if prices stay low. This could be a happy hunting ground for investors willing to handle cyclicality, cope with policy uncertainty and stay for the long term.

What are the risks that prices will not stay low? In fundamental terms, prices are linked to global growth. This cycle is changing. The latest IEA (International Energy Agency) reports indicate growing oil demand and depleting inventory. But shale and tight oil production will also ramp up to keep a ceiling on price rises. As prices rise, expensive shale operations become profitable and more supply comes in. There's a three-four month gap before shale can respond but there's lot of inventory to tide over that period.

Geopolitics is a much bigger threat. Some geopolitical explosion could lead to sudden supply constriction. The major exporters include Iran, Russia, Middle East North African nations, Venezuela, and Nigeria. Each of these places has seen major trouble and could see more in future.

In Russia's case, an undeclared war with the Ukraine has led to stress with the European Union and on/off sanctions. Venezuela is in chaos. Nigeria has an ongoing civil war with Boko Haram terrorists. ISIS, the Arab Spring and the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq has kept the Middle East and North Africa in turmoil. Iran has faced on/off sanctions.

In addition, evacuation of gas from Central Asia via pipeline to Karachi - the so called Turkmenistan-Afghan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline has been stalled for years. The latest issue is that many Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia, are demanding impossible concessions from Qatar. If that leads to a war or blockade, India's gas supplies will be affected since it has a long-term contract with Qatar.

Such risks are hard to assess. Commodity traders can try and take advantage of these by going long or short, as they think appropriate. The long-term investor can either ignore such risks or take a call if they have a good grasp of likely outcomes.