Goods and services tax (GST) became the order of the day on July 1, 2017. Much has been written about the advantages and the disadvantages of the tax. Hence, I will concentrate on another point, which I find hasn't been discussed enough in the media.

The rates of taxes that have been decided under the GST are 0 per cent, 0.25 per cent (for rough diamonds), 3 per cent (for gold), 5 per cent, 12 per cent, 18 per cent, 28 per cent and 28 per cent with surcharge. These are multiple rates of taxes, which in their own way, beat the entire purpose of having a value added tax (VAT) or as the Modi government likes to put it, one nation, one tax.

Also, a bulk of the goods and services will be taxed at 18 per cent, 28 per cent and 28 per cent with surcharge. As far as peak rates go, India's peak GST rates are one of the highest in the world, among countries which follow a GST/VAT form of indirect taxation. (See Figure 1). The question is why this is the case. The rates of taxes under GST on various goods and services were decided by the GST council. Their mandate was to fit the GST rate on goods and services close to the existing taxes. And that's precisely what they did.

Given that the existing taxes on many goods were high in the first place, the GST rates also turned out to be high. The question to ask is why the existing taxes were high in the first place. The answer lies in the fact that the tax-to-GDP ratio of India is pretty low when compared to the other emerging-market economies as well as to the developed OECD countries. Hence, the tendency is to squeeze as much out from those who are paying tax.

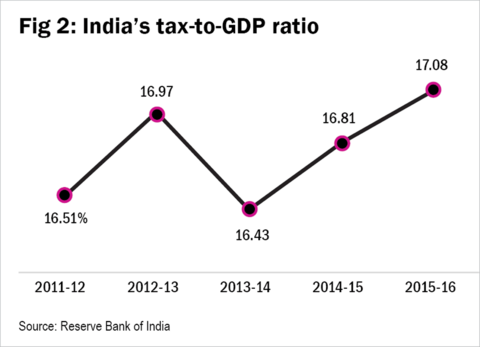

Take a look at Figure 2. It plots the tax-to-GDP ratio of India since 2011-2012. This includes direct and indirect taxes collected by both the central government as well as the state governments.

As is clear from Figure 2, the tax-to-GDP ratio of India has more or less been flat between 2011-2012 and 2015-2016, varying between 16.43 per cent of the GDP to 17.08 per cent of the GDP. The average comes in at 16.76 per cent. Ideally, we should have had a longer series for this analysis, but the new GDP data series goes back just to only 2011-2012. So, there is nothing one can do about that.

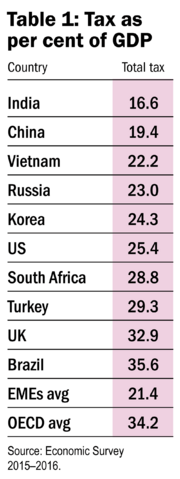

Now how does this data compare with those of other countries? Take a look at Table 1. It shows the data of the total tax collected by different countries as a percentage of their GDP. As is clear from Table 1, India has one of the lowest tax-collection rates in the world. China collects 19.4 per cent of its GDP as taxes. Brazil is at a very high 35.6 per cent. Emerging-market economies (EMEs) collect around 21.4 per cent of their GDP as taxes. The developed OECD (Organisation for Cooperation and Development) countries collect around 34.2 per cent of their GDP as taxes. Given this, India does not collect enough tax. And given this, it has what economists call a free-rider problem.

Governments create public goods which everyone can use. These include roads, railways, ports, hospitals, parks, airports, schools, colleges, universities and so on. These things are typically financed through taxes of various kinds. The government also pays the police, the judiciary and other entities which run the government. This infrastructure and the entities (good or bad) are available to everyone: those who pay taxes and those who don't.

The point is that public goods created by the government are available to everyone, even those who don't pay taxes or don't pay their fair share of taxes. Economists like to call this situation the free-rider problem. As Paul De Grauwe writes in The Limits of the Market: 'Individuals who decide not to contribute (and to be free riders) are in fact entirely rational from their perspective. After all, if the collective good comes into being, thanks to sufficient willingness among other individuals to pay for it, they will benefit because they cannot be excluded from its use.'

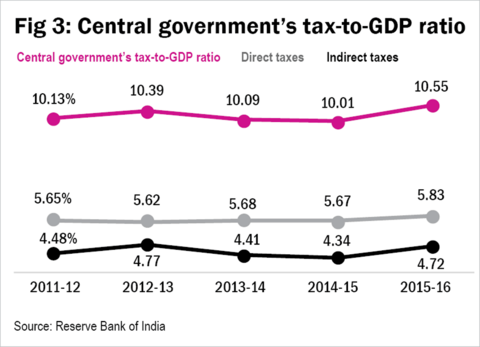

This is clearly true in the Indian case, with only a small section of the economy paying various kinds of taxes. This becomes clear from Figure 2, which shows that the tax-to-GDP ratio has moved within a small range over a five-year period. Take a look at Figure 3, which plots the tax-to-GDP ratio of the central government.

Figure 3 tells us that the tax to GDP ratio of the central government has more or less been flat (both direct taxes as well as indirect taxes). This essentially leads to a situation where the government has to continue to milk those who are already paying taxes. This is the prime reason which ensures that taxes remain high. This is especially true for indirect taxes, where the pinch is not as much as direct taxes. This also explains why the GST council did not use the available opportunity to lower the rates on different goods and services.

So, with the launch of GST, the government hopes to tackle the free-rider problem. Again, the question is how. Anyone who is claiming input-tax credit under GST needs to ensure that all his suppliers down the value chain have registered under this Act (i.e., have a Goods and Services Tax Identification Number, GSTIN). He also needs to ensure that he is in possession of an invoice from the supplier.

This will basically ensure that everyone down the value chain pays GST and ends up becoming a part of the formal economy. Theoretically, that just sounds fine. The trouble is that any firm which was a part of the informal economy and decides to go formal will not have to just deal with GST but with a whole host of rules and regulations, which hamper the ease of doing business in India. In this situation, the firms working in the informal economy may simply decide to shut down, given that it may not be viable for them to operate in the formal economy. Of course, no one really knows right now, how this is going to play out.