Lately, the Indian stock market has been marred by several instances of lapses in corporate governance. Companies like Vakrangee, Manpasand Beverages, Infibeam suffered massive falls due to poor corporate governance.

Such incidents especially hurt retail investors as they have only the financials reported by companies to analyse. If a company misreports its numbers, how can retail investors know about that? Is there any way to spot trouble in the making?

There are certain red flags that can help investors stay away from companies that face an uncertain future. These include high book profits but smaller cash profits, promoter pledging and suspect related-party transactions. This story revolves around assessing these measures.

In order to validate this method, we ran our filters on the listed space of 2016 and checked their returns in the next three years, as of 2019. Fortunately, we found the results of this back-testing satisfactory. We then went a step ahead and applied these filters to the current listed space. The companies that couldn't clear them are also listed in this story. These companies have a high probability of running into some corporate-governance issues in the future. So, beware.

We have presented this whole analysis in the form of a story to help you make better sense of it and also to make it more interesting. Here it goes.

Sharma ji Departmental Store

A little over three years ago, in April 2016, it was the start of the month and, as always, it was time for me to run to the grocery store for the monthly refill. I had my list of items ready, credit-card bill paid and renewed for a fresh round of expenses and now I just had to choose a place to shop.

I chose Sharma ji Departmental Store. It is a local kirana shop near my house and is run by Sharma ji, who is a family friend. Though I just called it a kirana shop, this store is actually huge and carries a range of items from imported perfumes to Ayurvedic toothpaste. Sharma ji looks after the store with a hawk eye and has a number of workers to support him. The store is always full of customers and it looks like Sharma ji has built a dominant position in the local market.

All these factors intrigued me. Sharma ji was thinking of opening more stores and wanted to professionalise the business. Being an equity analyst, I offered my services to Sharma ji and told him that I could have a deeper look into his business. I asked for the store's financial statements of the last five years to analyse the financial strength of his store and to understand how his business worked. At first, he was reluctant but on learning that I was doing this work for free, he happily came on board. Here is how I analysed the store's financials.

Turnover is vanity, profit is sanity, cash is reality

While looking at a business, investors generally focus on the book profits, when they should really be concerned with cash profits. What's the difference? Book profits don't imply a receipt of cash. A company can show book profits even when much of its profits are yet to be received in cash. Book profits can be manipulated by companies through aggressive revenue recognition policies. Cash profits, on the other hand, show cash that a company has actually got. Hence, cash profits are a better indicator of profitability than book profits. While it's okay to have book profits in the short term, a company should be able to convert its book profits to cash profits eventually, within a reasonable period.

I found that in the past five years, the store's sales grew by more than 20 per cent year on year. During this period, Sharma ji kept on expanding his list of offerings and also started a delivery service. He also increased his net profits by more than 20 per cent. All these numbers look really impressive. But the cash-flow statement had something else to say.

The cash-flow from operations (CFO) had been erratic year on year. On summing the last five years of CFOs and comparing them with the sum of five years of operating profit (book profit), the analysis showed that for every Rs 100 of reported book profits, the store generated less than Rs 60 of cash profits. This was strange, given the impressive profit-and-loss statement, so I dug deeper.

Sharma ji's cash flows showed a consistent rise in receivables, while the payables did not increase by that proportion. On talking to customers, I learned that on most occasions, Sharma ji didn't take immediate payment for the purchases made. I asked one of the customers why she loved shopping from Sharma ji's store. She said, "Sharma ji offers a range of items and along with that he runs a khaata (account), wherein he takes cash payments against bills after two months or more."

This was alarming as Sharma ji was resorting to aggressive sales but was not generating cash from it. What's even more concerning was that most of his suppliers were big distributors with whom it was just not possible to negotiate either on the payment or the time period.

Investor alert

The difference between book profits and cash profits is a red flag to be looked upon and analysed deeply by investors while investing in companies. While a company's conversion of book profits to cash profits might suffer due to genuine reasons also - like business expansion, lack of management's focus on cash-flow generation in comparison to profit-and-loss statement, industry trends, etc. - there are many companies out there that cook their books and show a fake picture to investors.

One way in which they do that is through aggressive revenue-recognition policies. By applying methods like channel stuffing (the practice of shipping more goods to distributors and retailers than end users are likely to buy in a reasonable period of time), extended credit period for customers, etc., higher book profits can be shown. Is this fraudulent? No. Accounting principles allow recording of revenues and expenses on an accrual basis, not just when actual cash is exchanged. The problem arises when a company is not able to translate these book profits into cash profits.

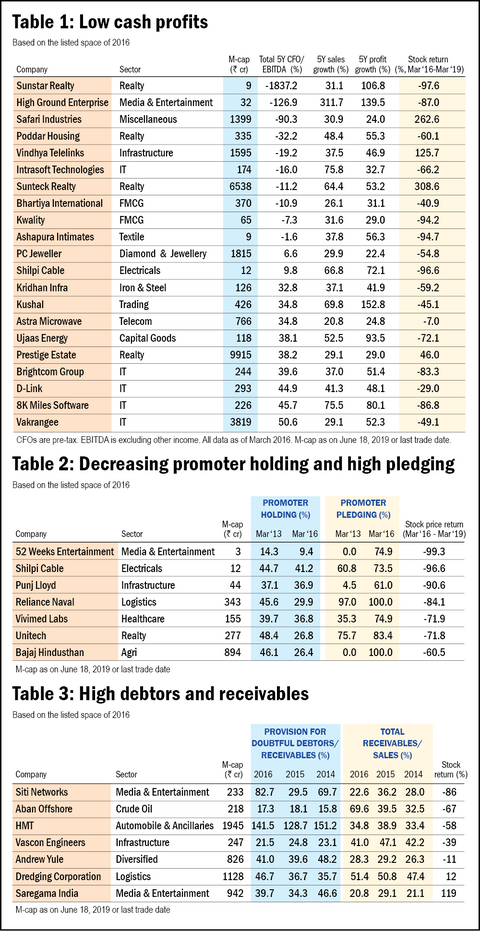

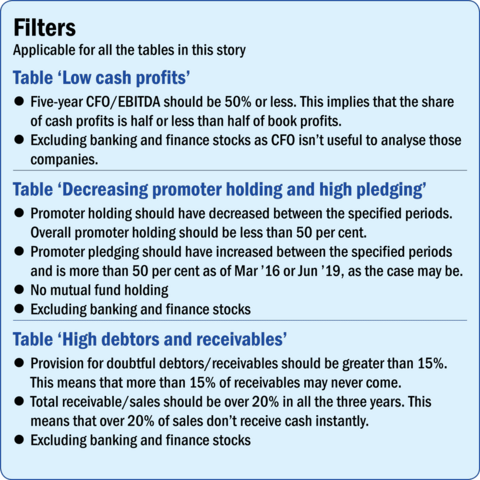

In the table 'Low cash profits' (Table 1), we have listed companies whose five-year cash profits (CFO) were 50 per cent of book (operating) profits or even less than that in 2016. The table also captures performance of the stock prices from March 2017 to March 2019.

Unfortunately, Sharma ji's business was not as foolproof as it looked at the outset. Maybe he was just in the expansionary phase and wanted to capture as much market as he could and that is why he was resorting to credit sales. Maybe he would make superior cash profits once he gained sufficient market share. With these thoughts, I went ahead with my analysis.

Skin in the Game

Sharma ji lived in in his own house, drove an expensive car, and from his Facebook profile, it seemed that he took at least one foreign trip a year. He also mentioned to me that other than the grocery business that he was running, he had rental income from his other properties to add to his total income.

This gave me the impression that Sharma ji was the sole owner of his business. However, I was surprised to find that he wasn't the only owner. He had started his business seven years ago. With a little capital of his own and the rest raised from four other partners, he had bought the land and built the store.

At the start of his journey, his total shareholding in the venture stood at 60 per cent, with the rest held by the four other partners. However, in the past three years he had sold part of his stake to the other investors. What was even more worrisome was that Sharma ji had recently pledged his share in the store with a local bank. When I asked him about the lowering of the holding and pledging of shares, he mentioned that it was meant for business expansion. However, from related parties, I found that Sharma ji had recently acquired a piece of land nearby and was looking for prospective buyers for it.

Investor alert

Here we observe another red flag which investors should pay close attention to while investing in any company. Promoter holding in a company is a sign of skin in the game. In the case of mid and small caps, especially, a high promoter holding shows that the interest and wealth of the promoter are aligned with those of the shareholders.

Another red flag to watch out for is high promoter pledging. Promoters can pledge their shares as collateral with a financial institution to raise money. Pledging is not always bad. Many times, promoters pledge their shares for a sound business reason and get them released later. However, a very high promoter pledge might also be a sign of bad management as the money raised could be used by promoters for their own personal use.

In recent times, the stock prices of companies like Kwality, CG Power and others have suffered due to the inability of the promoters to pay their debt, which prompted financial institutions to sell their pledged shares.

In the table 'Decreasing promoter holding and high pledging' (Table 2), we have listed companies that had high promoter pledging in 2016 and decreasing promoter holding. These companies have also proved to be wealth destroyers.

Stealing from my own locker

Having analysed the store financials, my initial fascination with Sharma ji's departmental store had started to come down. The incapability of the business to generate cash profits, along with Sharma ji's reducing interest in the business, made me doubtful about its future prospects. However, I continued my analysis and this time the focus was the balance sheet.

A few days back, Sharma ji had thrown a party to celebrate his son's graduation. I was also invited to it. During the party, I learned that his son had a business idea and wanted to start his entrepreneurial journey. I wondered if it was the lack of good jobs or a genuine entrepreneurial spirit which was leading young people to starting their own businesses. I congratulated Sharma ji's son anyway and moved on.

The balance sheet of Sharma ji's departmental store came to me as a shocker. Sharma ji had given out huge loans to a related party. At first I thought that these loans were given to a business-related entity and were in line with business needs. But I soon discovered an interest-free loan of `50 lakh given out to Sharma ji's son. I couldn't recall his business idea but now I definitely knew who his initial investor was.

This was a big red flag, which essentially meant that Sharma ji was stealing from his own company. In this balance sheet, I also noticed that not only were the receivables constantly increasing year on year, provisions for doubtful receivables were also increasing at the same time. This meant that some of his customers were simply not paying up.

Investor alert

Investors should pay close attention to the transactions between the company and its related parties. For a company, a related party could be its directors, key management personnel, subsidiaries and other such entities. Companies often seek to secure business deals or extend loans and advances to their related parties. Although such transactions are perfectly legal and can arise out of a genuine business sense - especially for companies operating in sectors like infrastructure and realty as these sectors mainly operate through subsidiaries - investors should pay close attention to such engagements as they have the possibility of creating a conflict of interest.

Take the example of Infibeam Avenue, an e-commerce company, whose stock price crashed by 70 per cent in September 2018 because of reports that the company had given out an unsecured, interest-free loan to a wholly owned subsidiary. Investors punished the stock as the subsidiary had no assets, so its ability to pay back the loan was suspect. The stock price hasn't recovered till date despite the company coming out with multiple clarifications.

From a balance-sheet perspective, if the provisions made for receivables as a percentage of debtors are increasing, this shows that the company is not able to convert its sales into profits. In simpler terms, the customers to whom it sold on credit are not paying up.

The table 'High debtors and receivables' (Table 3) lists companies which had high provisions for doubtful debtors and receivables in 2016. Also see how these stocks performed in the next three years.

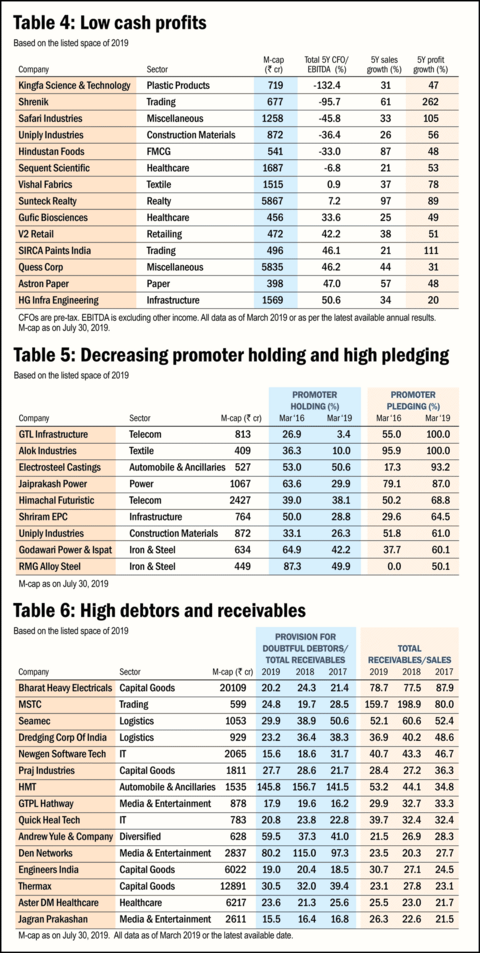

Finally, see the second set of tables (Tables 4 to 6) that mentions companies from the listed space of 2019. These companies may face corporate-governance issues going ahead, so research them thoroughly if any of them appear on your buying list.