Financial numbers are a reflection of management actions. While a competent management can bring a company unparalleled success on the back of its vision and passion, an incompetent one may sound the death knell for the company. The management is to a company as the captain is to a cricket team. M S Dhoni, who was a newly appointed captain, led the Indian cricket team in the 2007 T20 world cup. Backed by his vision and determination, the Indian team won the world cup. Similarly, when it comes to transforming a small business to a big brand, its management needs to march ahead with a bold vision and beliefs.

The ugly truth is most small companies either remain small or die. Only a handful of them break into the big league. Here we bring you the stories of five small companies that have turned large over the last 10 years. We have selected these five companies based on the growth in their market capitalisation over 10 years.

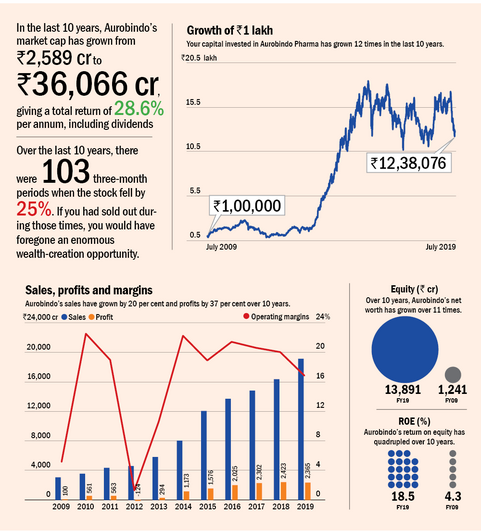

Hyderabad-based Aurobindo Pharma started operations in 1998-99 with one facility, at Pondicherry, manufacturing semi-synthetic penicillin (SSP). Today, it is the second-largest Indian generic pharma firm by prescription in the US and the tenth-largest generic company by sales in the world. It specialises in complex injectables and medicines for diabetes, AIDS, nervous systems and dermatology. It operates 11 units for APIs (active pharma ingredients; intermediates in drug manufacturing) and 15 units for formulations. Ten of those units are in India. It exports to over 150 countries across the globe.

Humble beginnings

The story of Aurobindo began in 1986 with Ramprasad Reddy, a purchase-department clerk, starting business by pledging his family's gold. In its initial years, Aurobindo manufactured and sold APIs in the domestic market. This was a low-margin, commoditised business. What propelled it into the envious position it is in today was its foray and specialisation in complex generics and injectables.

The transformation

The shift in Aurobindo's fortunes came in a gradual manner, in phases. The first involved Aurobindo focusing on high-margin generic formulations in the mid-2000s. Its strong API integration, especially its facility in China, supported the formulations business. The steady API supply cemented its position as a key formulations maker.

In 2005, the next phase of the transformation came with its entry into complex generics and sterile injectables for the US market. This was a period when the entire Indian generic industry was happy making copies of patented drugs. Aurobindo's entry into complex generics propelled it into advanced R&D and superior capabilities to manufacture complex drugs. By the time the party in the US ended for domestic players, Aurobindo was far ahead of most of them with its portfolio of complex drugs and injectables.

Navigating difficulties

Aurobindo's growth has not come without hiccups. Over the last decade, it has faced a number of issues. Back in 2012, it was named by the CBI in an investigation into a land-allocation deal, which had political undertones. The following year, the ED attached 96 acres of land and fixed deposits of Rs 3 crore of APL Research Centre, a subsidiary of Aurobindo Pharma.

More recently, in May this year, USFDA raised concerns regarding three of its units. Subsequently, one of those three units was issued a warning letter. The USFDA had also issued 10 Form 483 observations on one of its facilities in June. The warning letter will not impact Aurobindo much as it could shift production to its other facilities. The company has also said that existing business from this facility will not be impacted, though the warning letter would prevent it from any future approvals till the matter is resolved. The company was also named in a price-manipulation lawsuit in the US earlier this year, in which several other Indian generic firms were also named.

Going forward, the company could face a tough period if more of its plants are issued a warning letter or any get an import ban. The lawsuit will take its course in the meantime.

To get an early-mover advantage, high R&D expenditure hit Aurobindo's margins and profits. In its 2005 annual report, the firm said, "We see the quarterly results as a short-term score card. Actually, we work for the medium-to-longer term, map our goals, and work to create an architecture that enables us to contribute and play a role in advanced markets."

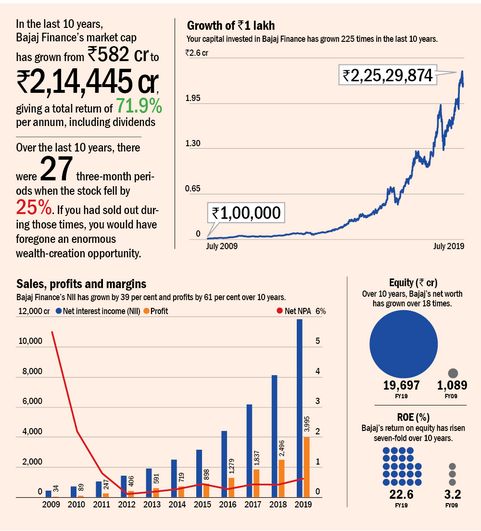

Financing for televisions, washing machines and refrigerators was a market most banks ignored. It is here that Bajaj Finance made its mark and went on to dominate the market. Today, a third of the nation's consumer-durables sales go through Bajaj Finance's network. It is also the second largest NBFC by market cap, with 3.5 crore customers and more than 91,000 distributors.

The great beginning

Bajaj Finance came into being after the demerger of the auto-finance business of Bajaj Auto in 2007. Sanjiv Bajaj, the man in charge, realised that the market for consumer-durable finance would take-off with a bang in India. One of his biggest master strokes was to appoint Nanoo Pamnani as vice-chairman. Nanoo is the former CEO of Citi India and Sanjiv's uncle. Nanoo brought his rich experience and is credited as the man behind the company's success.

Growth momentum

Bajaj has diversified into varied services and segments. It provides finance to consumers and SMEs. It provides services not earlier available to consumers. A loan approval, for instance, now takes 30 seconds - a long way from the five days it took earlier. The no-cost EMI does not charge interest to customers. The EMI card provides pre-approved loans to old customers. The Health EMI Network Card covers dental care, eye care, diagnostics and other treatments.

Risk management

Consumer-risk management is imperative for firms like Bajaj Finance to survive. More than 60 per cent of its customers have a CIBIL (credit) score of 750, suggesting the quality of its customer base. Its own analytics filter out bad customers from the good ones in seconds. Its strong dealer network and wide product base allow it to develop credit worthiness of customers. It has 20.7 million cross-sell customers all across the country (as of March 2019). They account for almost 60 per cent of its total customer base.

Bajaj's total loan book increased to Rs 1.16 lakh crore as of March 2019 from Rs 2,500 crore as on March 2007. It has also managed borrowings well, with inflows exceeding outflows. As a result, its return on equity has averaged at more than 19 per cent since 2011.

Bajaj Finance's success can be attributed to innovation that results in greater convenience. The company introduced innovative financial options like no-cost EMI and super-fast loan processing. In spite of its focus on speed, it has kept the risk low. It focuses on giving loans to those who currently don't want them, not to those who desperately require them.

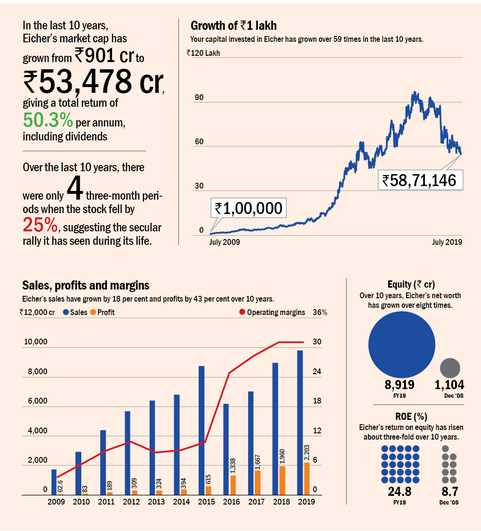

In 2000, when Siddhartha Lal, Managing Director of Eicher Motors, took over the reins of the company, it was losing money. Today, Eicher's Royal Enfield is the market leader in the 350 cc and above segment, sells more than eight lakh motorcycles a year and does business of close to Rs 10,000 crore.

Gearing up for the journey

Even as Siddhartha took the top job at Eicher, few had hope for its revival. The board even proposed to shut down the loss-making Royal Enfield division. Being a rider himself, Siddhartha understood the value of the brand and its bikes. In 2006, he decided to exit 13 out of 15 businesses of the group to focus on bikes and trucks.

Riding on transformation

Driven by his passion for bikes, Siddhartha turned around Royal Enfield with a bang. Riding it for thousands of kilometres, he found that its Bullet motorcycle had many deficiencies. It had an outdated engine and tech and required frequent repair. The most critical factor was that unlike normal bikes, it had gears on the right side that made it difficult for bikers to ride.

Siddhartha brought the technological changes while still maintaining the look of the older bike. With these changes incorporated, the Bullet Classic 350 and 500 were launched in 2009. These two models sold like hotcakes and had waiting periods of more than six months.

Eicher sold 50,000 bikes in 2010 and within four years, its sales increased by six times to more than three lakh bikes in 2014. By 2019, it had sold more than eight lakh bikes. The success of Royal Enfield created its own category of 350 cc bikes in India. Many global players tried their hand in this market but failed. Only two credible threats remain for Royal Enfield: the US-based Harley Davidson and Jawa, part of the M&M group.

Rising to the challenges

When the truck division was not doing too well, Siddhartha partnered with global auto major Volvo to manufacture and sell trucks in India. Volvo brought with it technological upgrade as well as financial muscle. By FY19, Eicher earned more than Rs 240 crore from this division, which was more than 10 times its total adjusted profit in 2006.

Eicher's journey from a small bike and truck manufacturer to a force to reckon with is reflected in its numbers. Revenues and net profit have increased by 18 and 43 per cent, respectively, in the last 10 years. Operating margins went up too, from about 4 per cent to 31 per cent. Its return on equity more than doubled from 9 per cent in December 2008 to 25 per cent in 2019.

Siddhartha Lal's marketing genius made the Bullet an iconic brand. He sponsored rallies and biking expeditions, which established the Bullet as an adventure motorcycle. The cult of the Bullet is such that there is a temple, called Bullet Baba, dedicated to it and there is a mechanic, Bullet Mani, who claims to identify any problem with the bike by just hearing its sound.

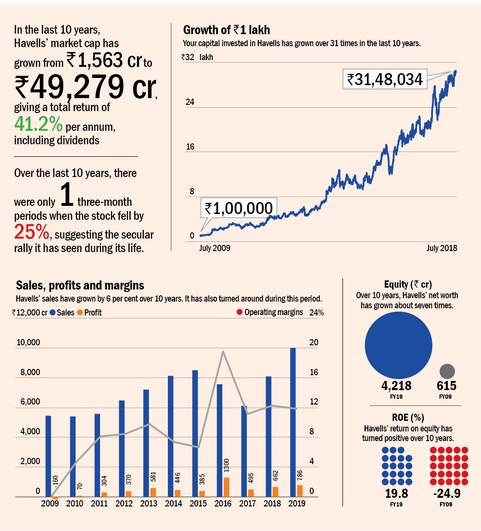

Havells India has come a long way from what the founder Qimat Rai Gupta started in 1958. Today, his small electric-trading business has transformed into a giant with a revenue of over Rs 10,000 crore and a market valuation of over Rs 45,000 crore.

Havells has made its name in circuit breakers, cables and wires, modular switches, air conditioners and other home appliances. The electrical-goods giant owns brands such as Havells, Lloyd, Crabtree, Standard and Promptec. It has a network of over 7,500 dealers and its products, manufactured in 12 plants, are available in 40 countries.

Its strong distribution network and add-on incentives, including insurance plans, guaranteed loans and investments in mutual funds to secure its distributors' future, act as strong motivators and ensure long-term commitment from its distributors.

Humble beginnings

In 1958, Qimat Rai Gupta started a small electric-trading firm in Chandni Chowk in New Delhi with Rs 10,000. He bought the Havells brand from Haveli Ram Gupta in 1971. That decision turned out to be momentous, as the company would go on to become the powerhouse it is today.

The transformation

The first four decades saw Havells morphing into the company we know it today. It started its own manufacturing plants, acquired a loss-making company in Delhi and turned it around, listed on the stock exchanges, competed fiercely with low-cost Chinese products, started its own research and development centres and acquired a number of brands. By the end of this period (2003), it had revenues of around Rs 300 crore.

The aim to transform itself from a switchgear and wire-maker to an electric-consumer-goods giant marked its next phase. Starting in 2003, this phase went on for the next four years. During this time, revenue was up 52 per cent; and profitability, 82 per cent. This phase also marked its biggest mis-step - the acquisition of the world's fourth largest lighting company Sylvania. This acquisition made Havells a global electric-goods giant with operations in over 50 countries. It also dragged its performance, tied down the management and sucked up all its resources.

Navigating difficulties

The boom years of 2006 and 2007 saw many Indian firms venture out to make mega global acquisitions. Most of them struggled later on. Havells snapped up the loss-making Sylvania in 2007. Top management set about restructuring Sylvania, which reported higher losses in the next two years. A number of factory closures and many layoffs later, Sylvania briefly turned profitable before going into red again. Havells sold Sylvania by the end of 2015. This move freed up the management and its resources to focus solely on India.

In the two years after the sale of Sylvania (since FY17), Havells' sales and net profits have jumped 1.6 times and return on capital employed has improved from 22 per cent to 29 per cent. It acquired the consumer business of Lloyd Electric in 2017, then the number two player in room ACs, to cement its position.

The company's success can be attributed to changing aspirations and higher living standards. These have resulted in a shift to modern switches, MCBs, etc. Also, Havells has effectively used advertising to create a niche for its products. Some of its advertising campaigns like 'Shock Laga' and 'Wires that Don't Catch Fire' were a huge success.

Motherson Sumi Systems

Vivek Chand Sehgal, the founder of Motherson Sumi, started off as a silver trader. Today the automotive-ancillary giant he heads in partnership with Sumitomo Wiring Systems of Japan does business of over Rs 63,500 crore and has operations in 41 countries worldwide.

Humble beginnings

Vivek Chand Sehgal started off as a silver trader. He spotted an opportunity in 1983 when Maruti Udyog (now Maruti Suzuki) was looking for an automotive-cable supplier. Trumping over 300 vendors, Sehgal tied up with the Japanese firm Tokai Electric to start supplying to Maruti. This marked the beginning of one of the most successful auto-ancillary companies in India.

The transformation

Motherson's jump into the big league can be traced to the string of acquisitions it has made over the years. So far, it has acquired 22 companies and turned all loss-making ones around. These acquisitions provide access to customers, markets, new products and technologies more easily than obtained organically.

Its acquisition of French car interior company Reydel Automotive last year provided access to carmakers Renault and PSA. PSA manufactures Peugeot, Citroën and Opel, among others. Reydel makes instrument and door panels, console and cockpit modules and decorative parts, etc. It has 20 manufacturing facilities in 16 countries. The Reydel acquisition expands Motherson's presence in Argentina, Croatia, Morocco and the Philippines.

Navigating difficulties

The company practises a 3C×15 strategy in which no country, customer or component accounts for more than 15 per cent of revenue. This strategy has helped it avoid major pitfalls. For instance, Volkswagen, a large customer, was found to be fudging US emission norms in 2015. Even though Motherson's stock took a beating, it was able to recover fast as Volkswagen accounted for just 12 per cent of revenue.

In 2005, when not many companies spoke about financial performancem, efficiency and shareholder interest, Motherson emphasised high returns on capital, positive cash flows and low leverage. It focused on funding dividends from free cash flows and ensured that acquisitions do not result in any dilution.

Motherson is also one of the rare companies that has remained heavy on debt while still servicing it and maintaining healthy cash flows. Sehgal has often quoted his mantra: revenue is vanity profit is sanity, cash is reality.

This strategy has translated into a return of equity of more than 20 per cent in all years except two, since 2003. The two remaining years were exceptional, given the cyclical nature of the automobile industry.

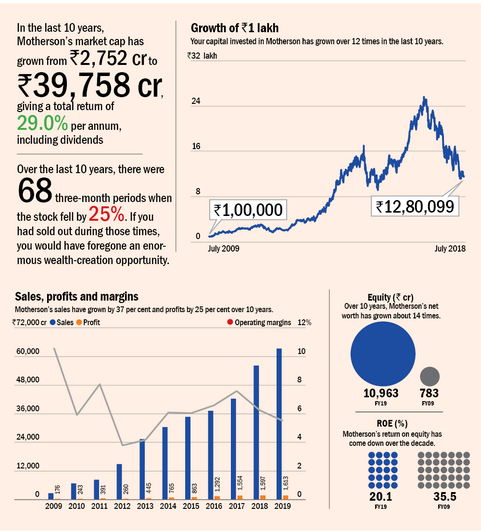

The focus on value-accretive acquisitions and the ability to turn loss-making ones around have profited Motherson well. Revenue and net profit have compounded by 37 per cent and 25 per cent every year in the last 10 years.

Motherson derives its name from the fact that it was started by Vivek Chand Sehgal and his mother. Interestingly, it was not set up to become an automotive-components company. The prime motive behind the formation of the company was to save taxes levied by the government on the silver-trading business.