The first page of 'The Economic Times' of March 16, 2022, emblazoned with the opinion of leaders of corporate India, stated, "75% of CEOs see moderate or no impact of war on economy". Going by the headline, it would appear that for us in India, global upheavals don't mean much. Even if they are as farreaching as sanctions on the Russian Central Bank, where, in an unprecedented move, the United States has frozen its foreign reserves. The Russian currency almost halved compared to early February, before recovering about half of the fall by mid-March. Sanctions against Russia are not new. In fact, before the latest round, Russia was already 'sanctioned against' by Western nations for its annexation of Crimea in 2014. What was different this time, however, was the freezing of assets of the central bank and the removal of Russian banks from SWIFT - a Belgian-based global messaging system for foreign-exchange transactions.

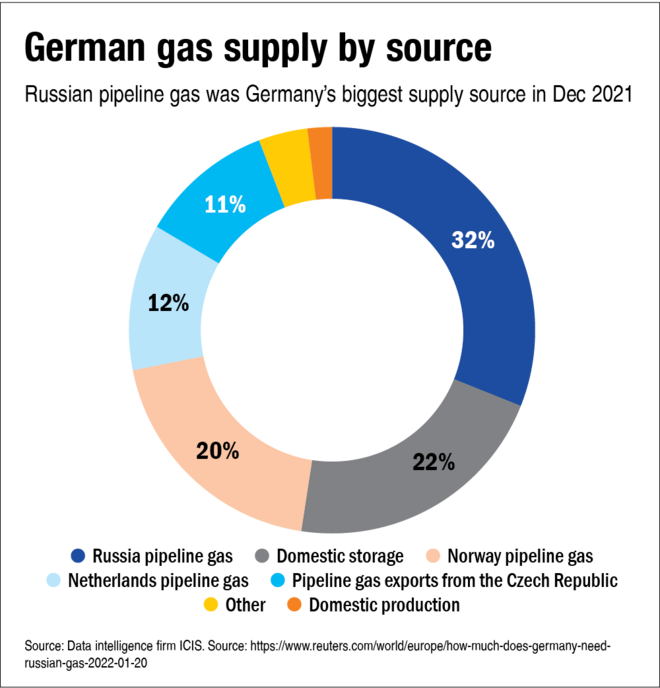

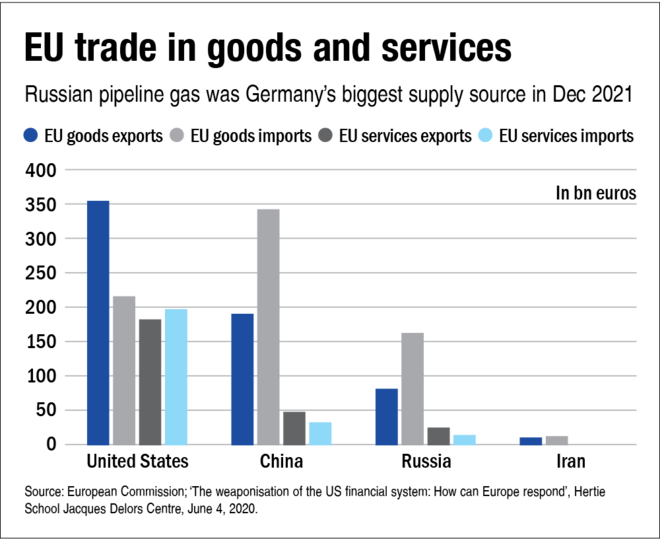

SWIFT disconnection is also not new - sanctioned Iranian banks were disconnected in 2012, but the trade impact for the EU and the US was negligible. Unlike Iran, Russia is a dominant supplier of energy to Europe - in particular to Germany - and supplies roughly a third of German and EU gas requirements. It also meets a third of German crude-oil requirements and over half of its coal needs. Despite the moral 'outrage' expressed at the Russian action against Ukraine, banks and entities that supply energy to the EU have been left outside the ambit of sanctions.

Secondary sanctions - an infringement of sovereignty

Primary sanctions refer to restrictions on economic dealings placed on companies and individuals from the sanctioning country with entities of the target country. Secondary sanctions, arising out of the USA's hold over the global financial system and its large market, restrict transactions between third parties and countries where the transaction has nothing to do with the USA. This form of economic coercion works simply because of the ability of the USA to penalise such companies and countries for not complying with its wishes. A relatively recent case that adversely impacted India was when the US imposed sanctions on Iran. India meekly complied with demands to reduce oil imports from Iran without receiving any benefits. In fact, it had to pay more for changing its supply chain - leaving China to benefit from subsidised oil imports from Iran. The US turned a blind eye to Chinese actions simply because its reliance on the Chinese economy was too large and sanctions would have hurt its own companies. Sanctions slowed Iran's COVID response by not allowing it to access medicines and hurt its populace. It impacted oil-importing countries like India. It induced Iran to start stockpiling nuclear material more than it had accepted under an earlier agreement - and it did not induce regime change.

The Trans-Siberian Pipeline - a case study of extraterritorial sanctions

The USA's single-minded pursuit of its own short-term interest often leads it to ride roughshod over the interest of its allies. In the early 1980s, President Reagan proposed sanctions against the USSR for its purported attempt to curb labour union protests in Poland. European countries were unwilling, citing lack of evidence of a direct Soviet involvement. Importantly, they had signed an agreement to set up a pipeline for importing gas from Russia - something that the US was opposed to. Unable to get its NATO allies to come on board, the US imposed unilateral sanctions against the USSR. These included licensing requirements on the export of oil and gas equipment, and restriction on such sales to the USSR. The Europeans wanted sanctions to be prospective as much of the pipeline equipment was from US companies. Instead, the US extended sanctions to not only US corporations but also their European subsidiaries.

Germany reacted with "the pipeline will be built", while France spoke of a "progressive divorce" from the US. The US further threatened to impose import tariffs on European steel producers for selling below cost and ignored its own embargo and allowed grain export to the USSR - hitherto banned. The sum of these steps reinforced the impression that the US was hypocritically defending its own economic interests while demanding sacrifices from others. The 'proof ' came in when Reagan managed to get Japanese firm Komatsu to stop selling pipe-layers to the USSR and within 10 days, granted a licence to export the same to Caterpillar - a direct competitor.

The British, and later the French government, ordered their companies to ignore the US threats and forced them to complete agreed-upon contracts. The US imposed sanctions on these companies, but they were soon lifted as the business for US firms dealing with the Europeans was affected. Faced with a unified Europe, the US unilaterally withdrew the sanctions against supply of goods for pipelines.

The current sanction

Not much seems to have changed with regard to sanctions against Russia and its supply of energy to Europe. The US is not a large importer of oil and if prices remain high, fracking can re-start to make up for domestic demand. Higher energy and food prices will impact the US less than many European countries. The negative impact will be felt in developing nations and poorer countries, many of whom, like India, are importer of crude, gas and fertilisers.

A simultaneous run-down of the US Fed balance sheet is likely to tighten global liquidity, leading to portfolios shifts from well-performing equity markets like India. High inflation, negative real interest rates and consumption growth that is tepid because of widespread job losses are not the best scenario for bullish markets. The expectation that private-sector capex will rise suddenly when the overall industry continues to operate at about 65 per cent capacity utilisation is also suspect.

As analysts tone down expectations of earnings growth in the current year, market valuations will remain elevated. In this environment, the view of the CEOs is surprising. Investors need to look at their own risk-return and investment horizon and not get carried away by bullish headlines.

Also read: